Riot Grrrl, Number 7: Difference between revisions

AubreeHamer (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

== Summary == | == Summary == | ||

A majority of the content | A majority of the content regards men’s depreciation of women. The content expresses how women have been repeatedly taken advantage of, judged for doing things men would normally do, and ultimately overshadowed by the patriarchy. Girls were forced to think that they were supposed to be kind or submissive to men so that they would be liked; however, men wanted women to feel naive and inexperienced. A majority of the content consists of poems or prose that feature women’s stories of being taken advantage of. The many women writing these works are fighting for their lives, bringing awareness to rape, going against stereotypes of sexism, and speaking out for women who couldn’t find their voices. On the contrary, some of the writing involves girls encouraging other girls to be themselves and stand out if that’s what makes them feel comfortable.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== Authors and Editors == | == Authors and Editors == | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Riot Grrrl Zines]] | [[index.php?title=Category:Riot Grrrl Zines]] | ||

Revision as of 06:17, 26 September 2025

Page Creators: Aubree Hamer, Chloe Cartwright, Hannah Crnkovich, Mea Cellitto, Samantha Summers

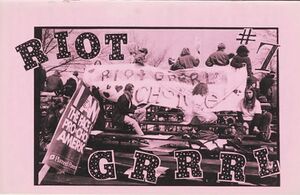

Riot Grrrl, Number 7 is a zine published in 1992 in Washington, D.C. There was no singular author or editor, but one of the contributors was May Summer Farnsworth.

Title: Riot Grrrl, Number 7

Date: 1992

Location: Washington, D.C.

Summary

A majority of the content regards men’s depreciation of women. The content expresses how women have been repeatedly taken advantage of, judged for doing things men would normally do, and ultimately overshadowed by the patriarchy. Girls were forced to think that they were supposed to be kind or submissive to men so that they would be liked; however, men wanted women to feel naive and inexperienced. A majority of the content consists of poems or prose that feature women’s stories of being taken advantage of. The many women writing these works are fighting for their lives, bringing awareness to rape, going against stereotypes of sexism, and speaking out for women who couldn’t find their voices. On the contrary, some of the writing involves girls encouraging other girls to be themselves and stand out if that’s what makes them feel comfortable.[1]

Authors and Editors

Many zines were compiled from letters, photos, flyers, and other media sent by riot grrrls through the mail. Riot Grrrl, Number 7 was created this way too; there is no single author or editor, but instead many contributors. Most of these contributors remained anonymous or only used their first names as identifiers. However, there are a few full names in the zine: May Summer Farnsworth, Heather Leach, and Stacey E. Lee are among them. [1]

There is not a lot of information on any of the contributors, except for May Summer Farnsworth. Farnsworth started Riot Grrrl Press with Erika Reinstein in 1992. It was established in Washington, D.C., where they printed and distributed various zines, including Riot Grrrl, Number 7. [2] She is now a professor at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, where she teaches Spanish, Latin American, and Bilingual Studies. She has written and contributed to several books and journals, including “We ARE the Revolution: Riot Grrrl Press,” and Feminist Rehearsals: Gender at the Theatre in Early Twentieth Century Argentina and Mexico. [3]

Context and History of the Zine

The Riot Grrrl movement was started in the early ‘90s by Kathleen Hanna and her band, Bikini Kill, to address the sexism in the punk music world. They wanted to rebel against the patriarchy by speaking their truths and their voices.[4] The movement soon spread to zines as a form for everyone to express their thoughts. The zines discussed multiple topics, mostly regarding rape, sexual assault, and sexism.[5] It was a political movement to empower women, especially in the punk world, and give them an outlet to relate with one another.[6] The Riot Grrrl zines were one of the first to be published and are significant to the underground movement, both in the writing and musical world.[7] The zine Riot Grrrl #7 discusses topics of sexism, sexual assault, rape, and the judgement men place on women.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 “Riot Grrrl, Number 7.” DC Public Library, 1992, digdc.dclibrary.org/do/80555ddc-1919-413b-a49d-8c8df075b9fe. Accessed 10 September, 2025, pp. 1.

- ↑ “About Riot Grrrl Press and Riot Grrrl Review.” Riot Grrrl Press, riotgrrrlpress.weebly.com/about.html. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ “May Farnsworth.” Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 12 Feb. 2024, www.hws.edu/faculty/farnsworth-may.aspx. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Hunter, L. (2025, January 2). What was the riot grrrl manifesto? Far out Magazine. https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/what-was-the-riot-grrrl-movements-manifesto/

- ↑ Hunt, E. (2019, August 27). A brief history of Riot Grrrl – the space-reclaiming 90s punk movement. NME; NME. https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/brief-history-riot-grrrl-space-reclaiming-90s-punk-movement-2542166

- ↑ Mika. “Riot Grrrl: The 90’S Feminist Punk Movement.” Substack.com, Lilith’s Paradox, 15 Jan. 2025, lilithsparadox.substack.com/p/riot-grrrl-the-90s-feminist-punk. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Jackson, A. (2022, July 17). Start a Riot (and a Zine), Grrrl. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/start-a-riot-and-a-zine-grrrl/