Braille

Inventor

Louis Braille (1809-52) was blind himself due to an accident in childhood. He attended one of the first schools dedicated to the education of blind children. In order to teach reading they had book with raised letters but this was impractical and bulky with limited knowledge. Braille was inspired by the code used in the military that was made up of raised bumps and dashed meant to be read with the fingers. In combat this allowed them to communicate strategy without divulging their locations. Braille saw the potential and the increased flexibility of this method. He then in 1824 had a refined system of with raised dots in certain combinations to create the alphabet. Later more tools were added to help visually impaired people read on their own and even write. His invention was not widely adopted until after his death but Louis Braille made a huge impact on reading and books for future generations.[1]

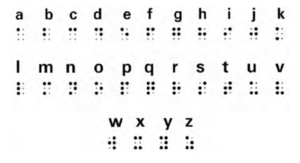

Braille Alphabet

A braille letter is made up of a six dots, some raised and some not raised in order to create the distinct identity of that letter. To the right is the full Braille alphabet.

Braille Publishing

According to LinkedIn the global Braille Book Market (which encompasses production, distribution, and adoption) it had an estimated value of USD 450 million in 2024. By 2033 it is estimated to grow to USD 720 million. Specifically in the United States the market is around USD 120 million in 2024, expected to expand to nearly USD 190 million by 2033. The market is doing very well and is dominated by call for educational materials and materials for public libraries.[2]

The first press to regularly publish Braille materials was the National Braille Press, located in Boston Massachusetts. It was founded in 1927 by Francis Ierardi. Francis was also blinded at a young age due to an accident and later in life realized the lack of materials for blind people. This set him on his quest to create a newspaper for the blind.[3] Read more about the NBP here.

The call for Braille materials also expands beyond books like educational materials and books for pleasure. An article in Publisher's Weekly more Braille uses were discussed specifically those serviced by the NBP. They included creating tactile graphics to help blind people understand different emojis, "brochures, tests, textbooks, business cards, airline safety guides," and also Starbucks menus.[4]

Impact

The Braille alphabet and Braille publishing allow millions of blind people and especially children read and learn. This gives them equal opportunity to learn and have access to the world of literature and the knowledge books hold. In an industry widely catering to those with sight it is important to remember that blind people also read and want to. It was a disadvantaged group in literacy for a long time and still is with the lack of materials.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Robinson, Solveig C. The Book in Society: An Introduction to Print Culture. Peterborough, Broadview Press, 2014.

- ↑ Customer Logic Insights. "United States Braille Book Market Size by Application 2025." LinkedIn, 13 Sept. 2025, www.linkedin.com/pulse/united-states-braille-book-market-size-application-tus3e/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2025.

- ↑ "Our Mission and History." National Braille Press, www.nbp.org/ic/nbp/about/aboutus/ourmission.html. Accessed 3 Nov. 2025.

- ↑ Stewart, Sophia. "How the National Braille Press Brings Books to Blind Readers." Publisher's Weekly, 21 July 2023. Publisher's Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/92816-how-the-national-braille-press-brings-books-to-blind-readers.html. Accessed 3 Nov. 2025.