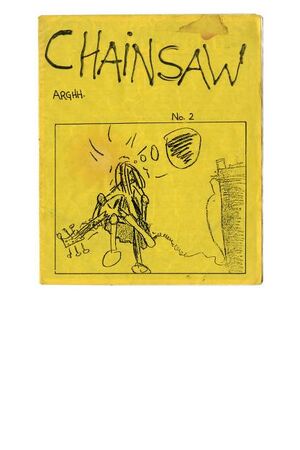

Chainsaw No. 2

Summary of Chainsaw No. 2

Information

About the Author

Donna Dresch possesses talents in many different creative fields, and through the art of music and zines, she has been able to make her mark on the queercore scene. Dresch made her debut with the fanzine “Chainsaw”.[3] But she didn’t stop there, as just a few years later she created her own record label called Chainsaw Records.[4] She went on to collaborate with many other people on their zines, and became an important name in the movement.[5] In addition to her zines, like many others in the Riot Grrrl sphere at the time, she went on to make music. Team Dresch is the name of the queercore band she founded.[5] It embodies many important things that were taboo in society at that time. Specifically, Team Dresch was composed of members who were all lesbians.[4] The band produced many songs, including ones that highlighted key issues often included in Riot Grrrl media, and they also collaborated with other woman led bands of the time.[5]

Background of the Riot Grrrl Movement

The term ‘punk’ is known as a rejection of societal standards, embracing anarchy and liberation. The Riot Grrrl movement is known in the punk scene as when punk was largely dominated by feminism, and established the core values and beliefs punk prides itself on today. Riot Grrrl was also instrumental in forming the ideals of third-wave feminism, in which women shifted away from creating political change and more so crafting individual identity, particularly in the male-dominated music scene.[6]

Before Riot Grrrl, women in rock scenes were treated as a novelty, and all female punk-rock bands became obscure as male punk-rock bands were propelled towards fame and idolized for their radical ideals. However, in the mid-nineties, artists such as Alanis Morisette, Fiona Apple, Tracy Bonham, and Meredith Brooks were popularized for their sexually explicit lyrics and catchy music, pushing them to the limelight along with their male punk counterparts. What set them apart from the women who came before them was their angry lyrics, expressing their constant frustration with the misogyny present in everyday life as well as the misogyny present in the punk scene.[7][8]

Riot Grrrl began in Olympia, WA and Washington DC in the nineties by Allison Wolfe and Molly Newman who coined the term. This meeting of women across the country was made to help women create their own space in the punk scene, oppose sexism all women faced in day-to-day life, and to directly oppose the hypermasculine ideals that punk touted at the time. This original meetup inspired many bands such as Bikini Kill and Bratmobile that helped spread the influence of Riot Grrrl across North America.[9]

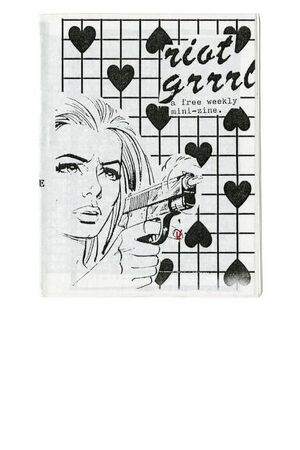

Zines played a large part in the spread of the Riot Grrrl movement. Homemade mini magazines were passed around communities, and allowed women from different economic backgrounds to get involved. It also promoted feminist art and the messaging of the Riot Grrrl movement.

Contextualization of Chainsaw in the Riot Grrrl Movement

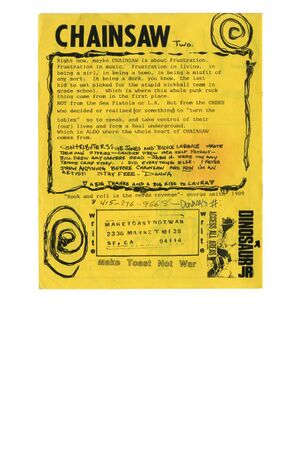

Chainsaw contains both print and doodles written in black pen, representative of how zines are a creative DIY effort that incorporates multi-media designs. The issue of Chainsaw shown above speaks about the frustration of girls who feel like they don’t fit in, including “girl[s]... homo[s]... dork[s]... the last kid[s] to get picked for the stupid kickball team.” They express their disconnection even in the punk scene whose whole purpose is to be a haven for counterculture. This is the big picture of the Riot Grrrl movement, the making of a punk scene for women who feel like the punk subculture excludes, overlooks, or fails to understand them despite its promise to accept all outcasts who speak truth about social justice. The authors of Chainsaw legitimize their frustration by pointing out that they’re doing the same thing as better known punk bands before them, like the Sex Pistols and the Creks by pointing out flaws in society and demanding change for their own wellbeing. Chainsaw claims its place in punk by reiterating the punk philosophy, that countercultural movements should be celebrated, respected, and used as a source of community.[10]

Citations

- ↑ Donna Dresch Discrography. https://www.discogs.com/artist/455771-Donna-Dresch/image/SW1hZ2U6ODk0NjEx

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Darms, Fateman, et al. The Riot Girl Collection. Internet Archive, 2013. archive.org/details/lisa-darms-johanna-fateman-kathleen-hanna-the-riot-grrrl-collection-the-feminist-press-at-cuny-2013/page/n17/mode/2up.

- ↑ Handley, Joel. “The Recording History of Early Queercore.” Reverb, 26 June 2020, https://reverb.com/news/recording-history-of-early-queercore. Accessed 12 September 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Doherty, Kelly. “Capturing the riot grrrl attitude in 10 records — The Vinyl Factory.” The Vinyl Factory, 20 August 2015, https://www.thevinylfactory.com/features/capturing-the-riot-grrrl-attitude-in-10-records. Accessed 12 September 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 “Biography.” TEAM DRESCH, www.teamdresch.com/bio-1. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Keene, Linda. "Feminist Fury -- Burn Down The Walls That Say You Can't." The Seattle Times, 21 March, 1993. https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/19930321/1691577/feminist-fury----burn-down-the-walls-that-say-you-cant.

- ↑ Salt, Veruca. "Veruca Salt - Seether Lyrics" Genius, https://genius.com/Veruca-salt-seether-lyrics. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Schilt, Kristen. "'A Little Too Ironic': The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians." Taylor & Francis Online, 01 Dec. 2010, https://modpub25.languagin.gs/index.php?title=Chainsaw_No._2&veaction=edit. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Hanna, Kathleen. "Bikini Kill." Kathleen Hannah Official, https://kathleenhannaofficial.com/projects/music/bikini-kill/. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- ↑ Farrington, Elizabeth. "When punk went feminist: the history of riot grrrl." Internet Archive, eb.archive.org/web/20201224041151/https://www.genrisemedia.com/2020/05/12/when-punk-went-feminist-the-history-of-riot-grrl. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.